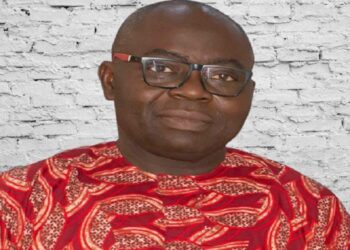

By Sylvester Onwudiwe

The assertion by some ignorant social media users that the Nigerian Civil War was solely caused by Ojukwu’s declaration of Biafra is a preposterous distortion of historical facts. It is imperative to correct such an unfounded narrative that disregards the intricate events and political tensions leading up to the war.

The Aburi Accord, a crucial peace agreement negotiated in January 1967, aimed to avert conflict by decentralizing power and granting regional autonomy. General Gowon’s failure to honour this agreement, despite Decree No. 8, was a key factor in the escalation of hostilities. Decree 8 was a flawed attempt at implementing the Aburi Accord, falling short of its provisions and failing to address the core issues of regional autonomy, as promised.

Furthermore, the claim that Ojukwu’s actions alone sparked the war is an insult to historical accuracy. The Igbo people had already suffered systemic ethnic violence, most notably the horrific massacres in the Northern Region in 1966, which claimed the lives of tens of thousands.

These atrocities, alongside Gowon’s eventual reneging on the Aburi Accord, set the stage for the war. To lay the blame entirely on Ojukwu while ignoring the calculated political moves and orchestrated attacks against the Igbo people is an oversimplification of the complexities that led to the conflict.

Lastly, the staggering figure of 3 million civilian deaths during the war, primarily due to starvation, is not some “monumental falsehood” as alleged. It is a tragic reality, supported by extensive research and global documentation. To diminish the scale of this catastrophe by presenting misleading casualty numbers is both irresponsible and dangerous.

The Nigerian Civil War was not merely the result of one leader’s declaration; it was the culmination of systemic ethnic violence, broken agreements, and calculated political manoeuvres aimed at subjugating an entire people.

To begin dismantling the erroneous claim that Ojukwu’s declaration of Biafra ignited the Nigerian Civil War, we must confront this baseless assertion with the weight of historical evidence. The idea that the war began because of Ojukwu’s unilateral declaration is not only misleading but deeply offensive to the gravity of the events that led to one of the darkest periods in Nigerian history.

1. The Aburi Accord (January 4-5, 1967)

The Aburi Accord was negotiated in Ghana between Ojukwu, the Military Governor of the Eastern Region, and Gowon, along with other regional military governors. The agreement aimed to ease the rising ethnic and political tensions in Nigeria following the coup and pogroms against Igbos in 1966. It included key provisions for regional autonomy, decentralization of federal powers, and mechanisms for resolving disputes peacefully. However, upon returning to Nigeria, Gowon faced significant internal pressure from military and political figures who were opposed to decentralization.

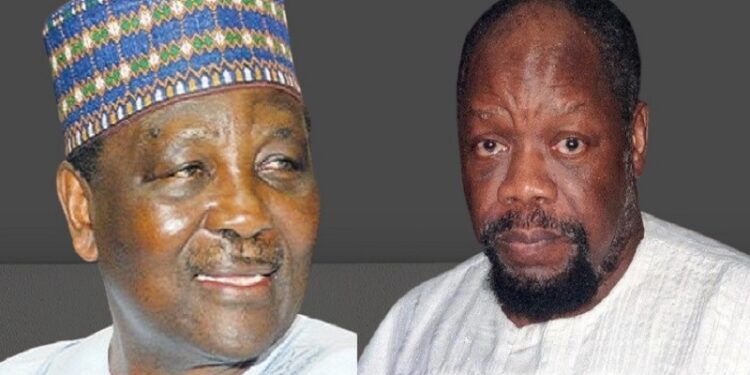

2. Brigadier Hassan Katsina and Northern Interests

Brigadier Hassan Katsina, the Military Governor of the Northern Region, was one of the major voices that pressured Gowon to reject the full implementation of the Aburi Accord. The Northern establishment, having already benefited from central control, saw regional autonomy as a threat to their dominance. The pogroms in the North, where tens of thousands of Igbos were murdered between May and October 1966, underscored the ethnic hatred that already existed. Katsina, along with others, believed that decentralization would weaken the Northern Region’s influence in the federal structure. Gowon, swayed by these arguments, began to backtrack on the accord.

3. Col. Murtala Mohammed’s Influence

Col. Murtala Mohammed, one of the leading military hardliners, also played a pivotal role in pushing Gowon away from implementing the Aburi Accord. Mohammed was deeply opposed to the idea of decentralization and feared that allowing the Eastern Region, dominated by Igbos, to become more autonomous would lead to the eventual breakup of Nigeria. His hostility towards the Igbo people was evident, and his advocacy for a military solution made Gowon reconsider the peaceful resolution agreed upon at Aburi. Mohammed’s stance reflected a broader anti-Igbo sentiment within the military, further inflaming ethnic tensions.

4. Chief Obafemi Awolowo’s Role

Chief Obafemi Awolowo, who was Gowon’s Vice Chairman of the Federal Executive Council and Minister of Finance, added to the political pressure. Awolowo, representing Western interests, supported the central government and feared that regional autonomy would lead to the breakup of Nigeria. Awolowo’s public warning in 1967, stating that if the Eastern Region seceded, the Western Region might follow, pushed the federal government into a more aggressive stance. His counsel to Gowon was a significant factor in the decision to abandon the full implementation of the Aburi Accord, even though it had been seen as a possible solution to the crisis.

5. The British Government’s Influence

Britain, Nigeria’s former colonial power, was also a critical external player that influenced Gowon’s decision. Britain had significant economic interests in Nigeria, particularly its oil reserves located in the Eastern Region. A decentralized Nigeria or a Biafran secession would have jeopardized British access to this resource. Consequently, British diplomats advised Gowon against decentralization and supported a military solution to preserve Nigerian unity. Britain’s backing emboldened Gowon to renege on the Aburi Accord, as he felt assured of foreign support for a military campaign against the East.

6. The Pogroms and Anti-Igbo Violence (1966)

Before the war officially began, there were organized killings of Igbos in the Northern Region. Between May and October 1966, tens of thousands of Igbos were massacred in pogroms, with many more fleeing the North to seek refuge in the Eastern Region. These attacks were state-sanctioned and reflected the deep ethnic animosity towards the Igbos. The violence was not isolated but part of a broader pattern of persecution aimed at weakening the Eastern Region. Gowon’s reluctance to stop the killings or hold the perpetrators accountable further signalled a systemic attempt to subdue the Igbos.

7. Decree No. 8 (March 1967)

On March 17, 1967, Gowon issued Decree No. 8, which purported to implement parts of the Aburi Accord. However, this decree fell short of the full decentralization agreed upon at Aburi. It was seen by Ojukwu and others in the Eastern Region as a betrayal of the agreement, as the decree still maintained significant central authority, especially in critical areas like military control and finances. Ojukwu rejected the decree, arguing that it was a deliberate attempt to undermine the spirit of the Aburi Accord and continue the marginalization of the Eastern Region.

8. Ojukwu Declares Biafra (May 30, 1967)

In response to the failure to implement the Aburi Accord and the ongoing persecution of Igbos, Ojukwu declared the independence of the Republic of Biafra on May 30, 1967. This declaration was a defensive response to the political and ethnic violence that had been directed at the Igbos, as well as the failure of the federal government to honour the promises made at Aburi. Ojukwu sought to protect the Igbo people and ensure their survival amidst the growing threat of extermination.

9. Gowon Orders an Invasion (July 6, 1967)

The Nigerian Civil War began on July 6, 1967, when Gowon ordered federal troops to invade Biafra. The invasion was not merely a response to the declaration of Biafran independence but part of a broader strategy to crush the Eastern Region and its people. The federal government’s blockade of Biafra, which prevented food and medical supplies from reaching civilians, led to the mass starvation of Igbos. This tactic, which some scholars have described as genocide, was aimed at breaking the will of the Biafran people by starving them into submission.

10. Casualties and Genocide

The Nigerian Civil War lasted until January 15, 1970, and resulted in the deaths of between 1 and 3 million Igbos. Most of the casualties were civilians, many of whom died from starvation due to the federal government’s blockade. The war was characterized by targeted violence against the Igbo people, including bombings of civilian areas, mass starvation, and atrocities committed by federal troops. The scale of the killing has led some to describe the Nigerian government’s actions as genocide.

Conclusion: Gowon’s Responsibility and Anti-Igbo Agenda

The Nigerian Civil War did not begin because of Ojukwu’s declaration of Biafra; it began because Gowon, under pressure from military hardliners, political figures like Awolowo, and external actors such as the British government, reneged on the Aburi Accord. The refusal to implement the agreement, combined with orchestrated ethnic violence against the Igbos, culminated in a war aimed at subduing the Eastern Region. The war’s strategy, particularly the use of starvation as a weapon, reveals an anti-Igbo agenda that sought to decimate the people and their aspirations for autonomy.

**Sylvester Onwudiwe is a public affairs analyst, an attorney and specialist in Corporate law based in the United Kingdom